WHAT A BOARD GAME TAUGHT ME ABOUT THE PANDEMIC

“Beijing needs to be quarantined.”

“Hopefully the scientists will be able to find a cure.”

“The R number is increasing!”

These aren’t excerpts from commentary on Covid-19. It’s my family discussing the crises that are emerging as we play the board game, Pandemic Legacy. We’d decided to jump in head first to see if the game taught us anything about the current global crisis. As in real life, the aim of the game is to control and eradicate diseases.

You may be thinking that playing a game like Pandemic Legacy, one that provides no escapism from our current reality, is the very definition of masochism.

But as I played, I was reminded of how games can be a good way to learn about how the real world works.

Consider Pandemic Legacy in relation to the current outbreak of Covid-19. When playing the game, you interact with concepts that are highly relevant to understanding the ongoing global crisis including:

R numbers. A way of rating any disease's ability to spread. Each player can affect this in the game.

Thinking in exponents. As the diseases spread in the early stages, it seems manageable, but then, all of a sudden, you are dealing with cascading crises.

Trade-offs. To solve one problem, you may reduce your capacity to work on another problem. Do you let an outbreak occur because you are instead focusing on building research centres to develop vaccines? Sound familiar?

What makes Pandemic Legacy distinctive compared to many other games is that it is cooperative rather than conflictual. Players have to work together if they want to successfully eradicate the disease. It’s a powerful lesson to comprehend, because that's how it works in reality, too.

This combination of learnings that could be applied in real life and the opportunity to develop collaborative problem solving skills stayed in my mind. Since then, I’ve been exploring the idea of what I call “gaming for good.” The use of games to improve how our society works.

Over the last decade, the popularity of gaming, especially amongst certain demographics, led some to speculate about whether games are the answer we’ve been looking for when it comes to improving civic engagement.

AOC livestreaming herself as she plays online murder mystery game, Among Us. Over 400,000 viewers watched along as she encouraged people to vote ahead of the 2020 US Presidential Elections

The theory of change goes something like this:

Games are super engaging and popular. Almost half the UK population - over thirty two million people - play video games. This includes a whopping ninety three per cent of children.

People are disengaged from politics. A survey of 14 nations including the UK found that beyond voting, “relatively few people take part in other forms of political and civic participation.”

By tapping into games and a learnt behaviour that people enjoy, you might be able educate people about political and social issues and demystify the institutional processes that people feel disengaged from.

And in doing this, players will become better informed as citizens and maybe they’ll be more likely to engage in the real-world. Whether that be voting or turning up to a local planning meeting.

It’s a nice theory. But as I delved deeper, I wondered whether such experiments inadvertently pointed to what I think are the under-explored opportunities in “gaming for good.”

Namely the use of games to drive collective action and overcome divides.

Let me explain.

Participation - which is a much-desired outcome in “gaming for good” - is no longer enough if we are to tackle the urgent challenges of our time. In fact, the crises we face demand two things from us.

First, that we all think about our everyday behaviour and choices. From Covid-19 to climate change, it’s clearer than ever that our individual choices impact the lives of others. While some of us are ignorant of this reality, others simply choose to ignore it.

Second, that we get better at communicating with other people, especially those that we disagree with. Long-term solutions need to be backed by consensus if they are going to be sustainable.

Games might be able to help with both by providing us with a safe environment where we can explore - and be confronted with the consequences of - our behaviour both as individuals and as a collective.

I’m going to explain how this might work in practice. Because inspired by my experience of playing Pandemic Legacy, and to take advantage of lockdown, I’m designing a game to test out these ideas.

You can look forward to:

From Games to Serious Games: A Very Brief History of “Gaming for Good” - a journey that I unexpectedly discovered stretches back almost half a century.

The Potency of Games: An Architecture for Engagement - an exploration of why games could help to drive collective action and overcome divides.

The Danger of Heavy Hands: Why Making Games for Good is Hard

Many advanced species, including humans, spend much of their early stages of their lives playing. It helps them make sense of the world, learning the skills they'll need to survive. The mistake of our societies has been the assumption that playing-as-learning is only meant for children. It's time to challenge this. Let's see how.

From Games to Serious Games: A Very Brief History of “Gaming for Good”

What is a game?

It seems so obvious. Some rules and scenarios in which you can win or lose. And of course, don’t forget fun.

But in the late 1960s, a new type of game began to emerge, one that most of us are unfamiliar with. These were games with an explicit educational purpose, that were not intended to be played primarily for enjoyment.

They became known as “Serious Games.”

Clark C. Abt, a sort of founding father figure for the serious games community, popularised the concept with his book, Serious Games, which he published in 1970. He wrote that games could offer, “a rich field for risk-free, active exploration of serious and intellectual problems.”

This wasn’t just a theoretical exercise for him. His company, Abt Associates, built serious games. One example was Fair City. In 1966, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson launched his “Model Cities Programme.” The aim was to develop new anti-poverty programmes and alternative forms of local government. It led to 150 five-year-long experiments across America.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development asked companies to propose games that “would abstractly but usefully and realistically represent the activities, procedures, and decisions involved in Model Cities decision-making systems.” Fair City, launched in 1970, was the result of this process. Involving 36 players, it simulated planning of a local development process over the course of a few hours.

So serious games have actually been around for a little while. The ability of games to provide an environment for learning, especially for adults, is often under-appreciated. This may be because of perceptions that gaming is bad for us in varying ways.

Popular critiques of games according to Wikipedia.

To give you a flavour of the types and nature of serious games, here are some examples:

Government Games. Exercise Cygnus was designed to test the UK’s pandemic preparedness. Over three days in October 2016, hundreds of UK officials faced a flu pandemic that affected 50% of the UK population and caused 400,000 excess deaths. It featured mock Cobra meetings, 24/7 coverage via a fictitious news organisation called WNN, as well as social media provided by “Twister.” Exercise Cygnus rose to prominence last year as Covid-19 first spread because the official report warned:

The UK’s preparedness and response, in terms of its plans, policies and capability, is currently not sufficient to cope with the extreme demands of a severe pandemic that will have a nationwide impact across all sectors.

Societal and Public Awareness Games. In Helsinki, city officials made a board game to help them think about how to involve citizens in their work. James Wallman’s “Hope Town” was a board game designed to illustrate the challenges of delivering effective social welfare with limited resources in Scotland.

Educational Games. Joel Levin, co-founder of Teacher Gaming, a company dedicated to using games to engage young people, was actually inspired by his own use of Minecraft in the classroom. As his students played, he saw they would build towns together, debate its governance and the use of finite resources. Another example of the use of games in education, is Synthesis School founded by the director of the school that Elon Musk built for his own children on the SpaceX campus. The curriculum has an emphasis on learning through team games and simulations.

The Future of Serious Games

This all got me wondering. What behaviour or issues might we want to explore within a gaming context today?

Here’s my starter for ten:

With so much debate about how to deal with disinformation, could you create a game focused on understanding and dealing with “fake news”?

With hundreds of millions of jobs set to be automated in the coming years and social norms that link our moral worth to our ability to work, could games help spark vital conversations about what the future of work looks like?

As we seek to tackle racism, could games help us to better understand concepts like institutional racism (which polling suggests the majority of people in the UK don’t) and unconscious bias?

Could we use games to illustrate how social inequality works? I’ve previously written about a study using Monopoly which demonstrated how you can deliberately overlook or forget the advantages that have helped propel you to where you are when you are doing well:

In this study, the games were rigged so that one person in each pair who played got twice as much money to start with, twice as much go money and got to roll both dice instead of one. When asked why they had inevitably won, the richer players didn’t highlight the privileges that they were randomly given in the first place. Instead they talked about what they’d done to earn success in the game.

Reading this, you may be thinking, surely there are better ways to tackle these kinds of problems?

Well, I’m glad you asked.

To answer this question, we need to understand why games are a powerful tool for learning.

The Potency of Games: An Architecture for Engagement

The starting point for understanding the appeal of games as a tool for learning is how engaging they can be. Their ability to drive engagement is highlighted by the influence of gamification and game design on a whole generation of tech products.

Consider gamification, the integration of game-like elements into business and marketing strategies to drive user engagement. Almost all of us interact with gamified products on a daily basis. Social media networks, for example, leverage likes and follower counts like points in a game to keep us hooked.

Unlike gamification, where you motivate users to behave in a particular way, game design starts from a desire to make something that people will enjoy. It’s a subtle, but critical difference - one that is worth taking a moment to reflect on as it goes to the heart of what makes a truly engaging game.

Rahul Vohra, CEO of Superhuman, a fast-growing email app, and a passionate advocate of games, summarises the aim of game design neatly, “when you make a game, you don’t worry about what users want or what they need, you obsess over how they feel.”

I saw what Vohra meant as I played Pandemic Legacy. When playing initially, my actions were rooted in a desire to achieve certain outcomes like preventing an outbreak. But as I played, I felt three things:

Connection to others with a shared purpose. This is built into the game - you have to work together.

Autonomous. While the game is collaborative, I was still able to make my own choices.

That there was scope for mastery. I became better as time progressed.

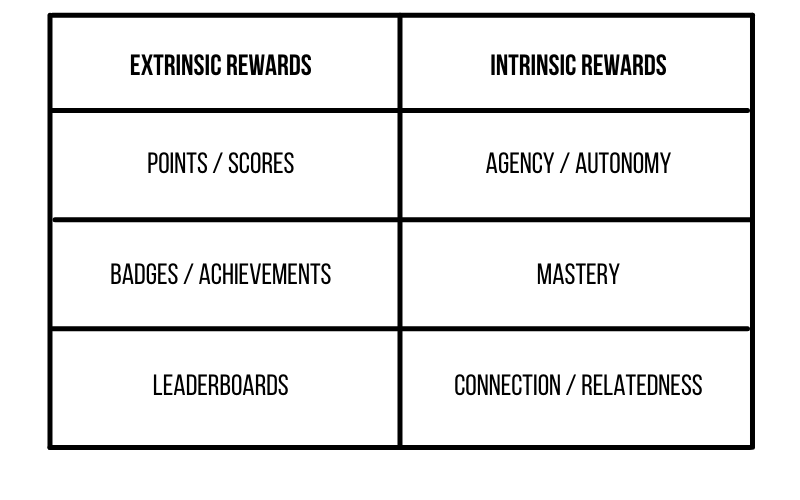

These feelings of connection, autonomy and mastery are the key to understanding why games are so engaging. They are intrinsic rewards. Unlike extrinsic rewards, they are intangible and relate to the internal psychological state of the player.

The left hand side includes typical features of gamification, while the right hand side are the feelings you hope to create through game design.

Such rewards can be incredibly motivating, generating a feedback loop where gamers play for further rewards. Players may even become intrinsically motivated, which means they engage in the activity for no other reason besides the love and joy of doing it.

I felt the tug of intrinsic motivation even after my family left, which meant that I couldn’t actually play even though I wanted to. All the while I was learning things and practising skills that could be applied to real life.

Obviously not all games are created equal in terms of their ability to motivate and reward us like this. But the potential of games to hold our attention amidst seemingly endless distractions is fascinating.

Consider news consumption. The Reuters Institute found that younger generations “do not want to work hard for their news.” In practice, news is often consumed on smartphones in small amounts to fit around other activities. Such consumption habits do not necessarily lend themselves to deeper engagement with the issues of the day.

As we’ve explored, this isn’t the case with games, which you can play for hours.

In the context of “gaming for good,” this creates opportunities to challenge participants' passive media consumption habits by using game environments to encourage them to actively engage with issues.

This engagement helps to create the conditions for what excites me most about games, their ability to improve our capacity for collective action.

Games as a Unifying Force

We live in a culture that celebrates lone individuals who have defied the odds to achieve incredible feats. Think about how Elon Musk is revered on the basis that he seems to be single-handedly driving us on to colonize Mars. His influence is such that he can move markets with just a few words.

This is no different from our past, when individuals who were strong or wise had a higher status in a tight-knit tribe. But what has changed is the megaphone through which these stories are told. In the opening of Gladiator, Maximus famously says, “what we do in life, echoes in eternity.” But thanks to technology, tales of individual ingenuity echo across the world almost immediately.

Amidst all this, it’s easy to forget that almost everything we’ve achieved as a civilisation is the result of groups of people working together.

And this is why games are magical. They can bring us together, especially when collaborative game dynamics as seen in Pandemic Legacy are used. As James Gee, an academic who has studied collective intelligence writes,

...human minds are plug-and-play devices; they’re not meant to be used alone. They’re meant to be used in networks.

By playing games, we can improve our ability to collectively solve problems. Let me show you examples of how they might do this:

1. Game environments could help us see the impacts of our individual behaviour and the lives of others, strengthening our ability to act collectively.

If events or issues don’t touch our lives, many of us naturally feel less compulsion to be as engaged or to change our behaviour. This is problematic when the transformation that needs to happen requires that we change our individual behaviour. Take Covid-19. As I previously wrote:

If you are from a higher socio-economic background, have a low risk and are able to safely distance ... you may be more likely to emphasise the economic costs of the lockdowns or the loss of freedoms rather than a continued need for strong public health measures.

Games could be designed to allow participants to reflect on how their individual preferences impact the collective by bringing issues that we may lack direct experience of to life. By highlighting the downsides of individualism, game dynamics could be used to strengthen our capacity for collective action.

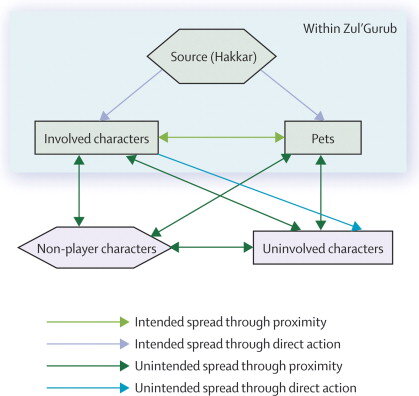

An epidemic that took place in 2005 offers an example of what might be possible. This epidemic took place in the confines of World of Warcraft, a massive multiplayer online role-playing game. The creators released a game update with unintended consequences.

It allowed powerful players access to an area where they would do battle with a villain. They would sometimes be infected by a disease called “Corrupted Blood,” which had little effect on these players, but weaker players were not so lucky.

A few factors quickly transformed what was meant to be a minor hindrance into an epidemic. First, many characters could transport themselves instantaneously from one location to another, meaning the disease spread. Second, the disease could be carried by pets outside of the area. Third, non-player characters could catch the disease but not die, so they were effectively asymptomatic spreaders. Millions of players were infected.

Chain of infection of novel virtual pathogen, World of Warcraft, September, 2005. The Lancet.

In response, the creators tried to impose quarantine measures with the support of some players, who also used their powers to heal infected players.

But all these efforts failed because of the contagiousness of the disease, their inability to comprehensively seal borders, as well as player resistance to the measures. In the end, they simply reset the game without the “Corrupted Blood” feature.

The story resurfaced recently as it provided a fascinating - and very much accidental - case study into the sociological dimensions of an epidemic that foretold some of the very challenges we currently face in relation to Covid-19. Looking beyond how such games could serve as a bridge between epidemiological studies and reality, you can quickly see how such an environment might be used to get players to reflect on the impact of their individual choices.

2. Games can help us to challenge biases which impede our ability to act now in order to safeguard the future.

Throughout our history, it’s made sense to focus on what might kill us immediately rather than in the distant future. In doing so, we’ve evolved a cognitive bias whereby we perceive the present as more important than the future. Known as hyperbolic discounting, this bias means that we struggle to take actions today that might head off complex challenges in the future.

One example where we can see this bias in action is in relation to climate change. There is an increasing consensus about how the worst-case scenarios will change life on earth. But for many of us, the realisation of these scenarios is still some decades away. Just as our ancestors evolved a preference for sweet-tasting calorie-rich fruits, we also want to enjoy the fruits of living today. That’s partly why there is a strong relationship between income and per capita CO2 emissions.

Game environments can counter hyperbolic discounting by showing us how decisions taken to combat climate change today (or our inactivity) may shape the future. This ability to see the consequences of our decision-making in a compressed timeline could help to shake us out of complacency by forcing us to consider where status quo leads to.

3. Games could be used to support local communities to imagine small-scale solutions to complex issues.

In Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, Sebastian Junger writes that:

If the future of the planet depends on, say, rationing water, communities of neighbours will be able to enforce new rules far more effectively than even local government. It’s how we evolved to exist, and it obviously works.

In other words, taking collective action in a smaller community might be easier because the desired behaviour is on your doorstep. Adherence to behaviour is reinforced by social pressure as everyone knows each other. Unlike larger communities where we don’t know - or trust - everyone.

Local collective action could also unlock what is known as the endowment effect. This is where when we own something - even an idea - we tend to value it more. All of these factors explain what David Fleming was getting at when he wrote that:

Large-scale problems do not require large-scale solutions. They require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework.

If collective action might be more effectively taken at the local level, a game environment could be a tool to give communities agency to come up with solutions.

So games keep us engaged and could be used to make us better at solving problems together. But emerging research shows a path forward for how games might also be designed in a way that makes us better at communicating with other people, especially those that we disagree with.

Learning How to Disagree Through Games

Amidst the cacophony of commentary decrying polarisation, it’s easy to forget that disagreement is healthy. It’s how we develop our best ideas. As Ian Leslie, author of Conflicted: Why Arguments Are Tearing Us Apart and How They Can Bring Us Together, writes, “instead of putting our differences aside, we need to put them to work.”

Gaming could provide the perfect environment to put our differences to work. Compared to the glare of social media, a game environment could offer a safer, less high-stakes, context in which to discuss complex and challenging issues.

It’s well-documented, for example, that arguments on specific issues can quickly escalate into wholesale identity conflict. As Leslie notes, “arguments are a way of signalling who we are.”

But in a game, you can detach the individual from perspectives that they are closely wedded to by allowing them to play different roles. This roleplaying can allow gamers to take on and explore different perspectives in a game much more easily than in real-life.

Games can also be engineered to integrate tactics that we know are likely to create opportunities for greater understanding between participants.

Recent research suggests that the way to build mutual respect with someone who disagrees with your perspective is to share your personal experiences of an issue rather than relying on facts. If you are anti-guns because you've experienced gun crime that will carry more weight than talking about statistics that show a correlation between gun ownership and firearm homicide rates.

Games could be intentionally designed to get participants to share their experiences of an issue in this way as a means of building bridges. As one of the villains in Batman Begins remarks, “you always fear what you don’t understand.”

But having set out how gaming environments could be used to improve our capacity for collective action and help us to overcome divides, caution is warranted.

The Danger of Heavy Hands: Why Making Games for Good is Hard

Making games is hard. Making games that tackle complex social issues and our behaviour is even trickier in some ways:

1. When educational purposes are the driving force rather than having fun, the learning experience may not be as powerful.

I’m not interested in being told things or asked questions about myself by videogames, not because of my self esteem, like I don’t feel like I deserve the attention, or my fear, like I might learn something about myself I don’t like, but because I’m asked and I answer questions about myself all the time, every day, and they’re almost always more searching than anything a videogame has so far ever thrown at me…

The best educational experiences in gaming are often a byproduct of being engaged and having fun, as I was when I played Pandemic Legacy. I didn’t primarily play because I wanted to learn about pandemics.

When it comes to serious games, players know the main purpose of the experience is to learn something, not enjoyment. But even when armed with that knowledge, the experience may not be as transformative as it is when the educational purposes are secondary - or more subtle.

Recall what Rahul Vohra said about game design: “when you make a game, you don’t worry about what users want or what they need, you obsess over how they feel.” When making games like this, it will be harder to get the balance right, between what players need (i.e. to learn about X) and what they feel.

As Andy Matuschak, a renowned software engineer and designer, writes,“... [in educational games] the ‘teacher's’ hand is usually too heavy; players feel like helpless rats in someone else’s maze.”

2. You have to make difficult choices in representing what you seek to question - in doing so, you may offend people.

When making games that deliberately mirror reality as a means of better understanding and challenging it, one question that quickly comes up is this: how accurate should the representation of reality be?

Think about my suggestion that we could use games to better understand concepts like racism.

There have actually been interesting albeit half-hearted attempts to do this. In South Park’s: The Fractured But Whole video game, players used a difficulty slider to change the colour of their skin. The darker your complexion, the harder the game. There was a limit to the amount of money you could make in the game and how other characters interacted with you changed.

Put aside the risk of trivializing serious issues for one second.

If you were serious about making players think about racism and reflect on their own behaviours in the way I set out, you’d couldn’t just take racism at face value as was the case in South Park. You’d have to provide context like history that allowed players to learn. And in doing so, you’d then have to decide how much to include, how far to go back?

This in itself would be a fascinating educational experience for game designers. But it would be very easy to go wrong both in terms of the pre-game design, as well the actual playing experience (i.e. you may feel the heavy hands that Matuschak wrote about).

3. It’s unclear what winning or losing looks like in “gaming for good” and a “win” may even be boring resulting in undesirable behaviour.

Do you really want to consider complex social problems through a win-lose dynamic, pitting players against each other in competition? Collaborative game dynamics like the ones employed in Pandemic Legacy can help overcome this. But even then there are unintended consequences that might be unleashed in a game environment.

First, players might simply just play to win in the context of the game, with none of the behaviour exhibited in the game carried over into real-life.

Second, as in real-life, when it comes to complex issues, there isn’t always a clear outcome that lends itself to the type of win or lose situation that many players desire. This can lead to absurd behaviour.

This was observed even in one of earliest examples of serious games, The Most Dangerous Game. First released in 1967, it aimed to get players engaged with foreign policy by allowing them to roleplay as countries in historical moments such as the creation of the League of Nations and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Despite being an unlikely course of action in real-life, play always ended in nuclear war. The game designers noticed that the players grew bored of the stalemate that almost always occurred in the game. The result was nuclear armageddon.

Ready To Play?

Our culture is awash with tales that explore morality through the means of a game.

In Ender’s Game, a classic science-fiction novel, children are tricked into committing a genocide because they assume they are only playing a game. In Ready Player One, gamers search for an Easter egg that would allow them to take control of the OASIS, a virtual reality world akin to Second Life. The protagonist leads an army of avatars against a powerful corporation that wants to exploit the money-making opportunities within the OASIS. And in The Hunger Games, children are selected via lottery to participate in a compulsory battle royale that is televised to remind participants and the places that they come from, of their powerlessness.

What I’ve explored is actually not too dissimilar. It’s about the use of games to better understand ourselves and the societies in which we live.

This isn’t science fiction anymore. These tools are already being developed.

While I’ve explored board and video games, I’ve not touched on technologies like virtual and augmented reality, which offer possibilities that early designers of serious games could only dream of.

Take a look at Improbable’s “synthetic environments,” which offers to support policy makers by allowing them to tackle issues in a virtual world before taking action in the real-life:

What might be possible if we democratise the use of such tools by putting them in the hands of ordinary people?

There are valid questions to be asked about whether using games in this way is a distraction in light of the severity of the generational challenges that stand before us.

But despite there being hurdles to overcome and some doubts, there are plenty of signs that games can bring complex social issues to life for participants in a way that is more engaging than the status quo.

I suspect that starting with individual behaviour in a gaming environment could be a more compelling way to drive real-world change, especially as it is closer to how we conventionally experience games.

So if you’re interested in learning more and maybe even helping me to test these ideas, get in touch.